By Jodi Ploquin and Elizabeth Krivonosov

In the words of Sidney Dekker, an expert in learning from adverse events, “the key to an investigation is not to point out where people went wrong, but to understand how their assessments and actions made sense inside that situation at the time.”1

As the laser safety officer, key elements to the investigation phase include:

- Visit the location where the event took place

- Interview those who were there at the time of the accident

- Take pictures; capture the scene

- Get a clear explanation of the work being done (consider process mapping)

The new view of safety challenges findings reported in the literature, such as 67 percent of medical laser accidents are attributed to operator error and demands that we look deeper into why these errors were made2. In the words of Trevor Kletz, “listing human error as the cause of an accident is about as helpful as listing gravity as the cause of a fall. It may be true, but it does not lead to constructive action. 3

To truly learn what contributed to the event, the laser safety officer must ensure ‘psychological safety’ of the individuals being interviewed. It is essential that the message be clear that this is a non-punitive process, with the focus of learning and improving, and that messaging is consistent from the manager level to senior leadership.

As in nearly any adverse event, one can point to a procedure or policy that was violated; it is often the first reaction of leadership to suggest that the individual who violated that procedure be held accountable. In deciding whether or not this is appropriate, an important test, known as the ‘substitution test’ is conducted. This involves asking the question whether another individual with the same information under the same circumstances might have made the same decision. If the answer is yes, then it is not appropriate to look at individual performance, but rather to look at the system in which the event took place.

Investigation & Analysis of Incidents

The following example is roughly based on Incident no.7, reported to the British Medical Laser Association, and discussed in the paper by Moseley2:

Scenario 1: “Description: Laser used in conjunction with a bronchoscope, LPA was called because a registrar had corneal damage. The procedure had taken about 1 h. Registrar claimed she had worn the glasses. The glasses and equipment were tested and found to be in good order. Follow up and outcome: The scarring resolved and the problem was never solved. No legal action followed. The totally unfounded suspicion of the LPA is that the glasses were abandoned and optimism relied upon instead.”

Concluding that an injury occurred because laser protective eyewear was not worn may be true, but does not lead to constructive action. If one explores why the laser protective eyewear was not warn, a host of reasons could surface;

- laser protective eyewear does not fit comfortably

- laser protective eyewear color distortion interferes with view of biological tissues

- laser operator wears prescription glasses, eyewear does not fit over his/her glasses

- laser eyewear for multiple lasers is stored in one drawer, making it is possible to select the incorrect eyewear

- the manufacturer (‘expert’) from the company never wears laser protective eyewear when he visits the site

Each of these reasons leads to a different corrective action.

Why-Why Method

One method used in patient safety is the “Why-Why method,” where you repetitively ask “why” to arrive at the deeper rooted factors that led to the event. In this example, we might ask:

Q: Why was LPE not worn?

A: “It was not available.”

Q: Why was it not available?”

A: “We don’t know what to order.”

Q: “Why don’t you know what to order?”

A: “The nurse that was our laser safety expert left our team, and no one has replaced her.”

We see by drilling deeper, buying an additional pair of laser protective eyewear would not have resolved the main underlying issue of not having a laser safety specialist supporting the surgical group.

Constellation Mapping

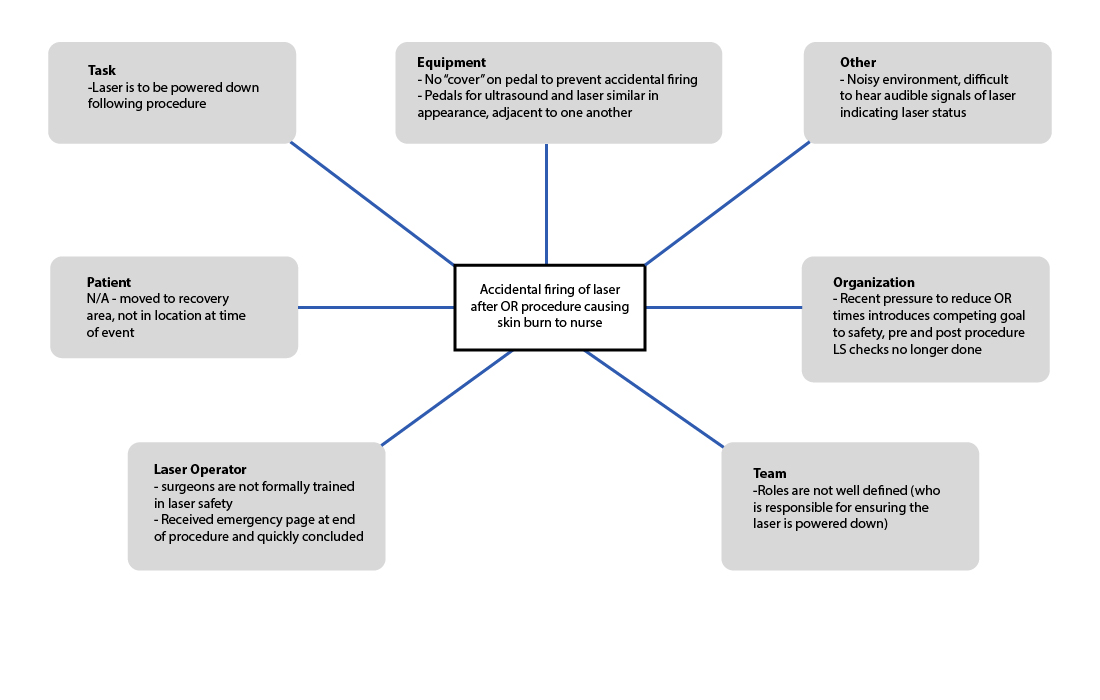

A method of analyzing adverse events, known as a ‘constellation mapping’ guides the analysis team to consider how various factors contributed to the outcome:

- patient

- health care provider (laser operator)

- team

- organization

- environment

- equipment

- task

This method, introduced in the Canadian Incident Analysis Framework, is a powerful tool in shifting from blaming individuals (“operator error”), to identifying systems fixes that will prevent future adverse events.4 This type of ‘systems’ accident model replaces earlier models that sought out a single ‘root cause.’ The findings can then be organized in to a matrix format i.e., constellation map, as shown in Figure 1.

![Figure 1. Constellation map framework [4]](https://www.laserstoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Figure-1.png)

It is important to conduct this exercise as a team, to include key perspectives such as a nurse and physician perspective in the health care setting.

The following example is roughly based on Incident no.7, reported to the British Medical Laser Association, and discussed in the paper by Moseley2:

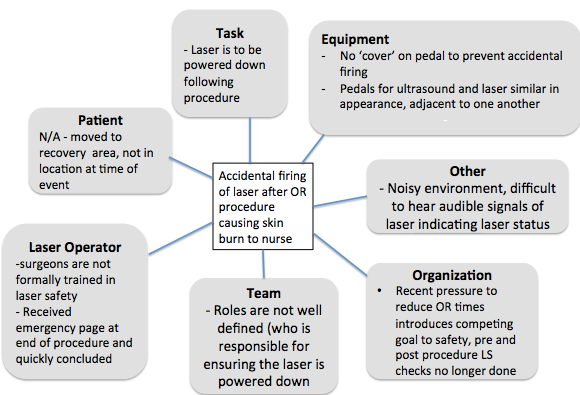

Scenario 2: A laser was fired after a surgical procedure was concluded, when an OR staff cleaning up the OR stepped on the laser pedal, resulting in a skin burn to a fellow nurse who was also in the area.

Rather than quickly concluding that this was operator error (forgetting to put the laser in standby after the procedure), interviews with the surgical team will allow the review team to build a deeper understanding of contributing factors. It is essential in interviews to emphasize that this is a non-punitive process with an emphasis on learning. The shifting of focus to the individual operator to the system, is known as “Systematic Safety Analysis.” A thorough guide for this approach is available online from the Health Quality Council of Alberta.5

In the example of the ‘accidental firing,’ one might find the following through interviews:

- The laser pedal does not have a safeguard that would prevent accidentally stepping on ‘fire’ button.

- The pedals for the laser and ultrasound are side by side, misfiring of the laser is not uncommon, this is just the first time it lead to injury.

- There is no formal laser safety training for surgeons who operate lasers – surgeons visit a site to learn how to use the laser from an experienced surgeon, followed by a period of support from company rep.

- Onsite training records show only nurses have attended laser safety training sessions.

- The audible indicators that the laser is in the ‘ready’ state are difficult to hear in the noisy or setting.

- Organizational pressure to reduce OR time, pre and post procedure LS checklist no longer done.

- The surgeon had received an emergency page as the procedure was ending.

- Nurse A thought the surgeon had powered down the laser before leaving. The surgeon is used to working with Nurse B who always takes care of powering down the laser at the end of the procedure.

The populated constellation map for Scenario 2 is shown in Figure 2.

We now have a much richer understanding of the factors that contributed to this event, and many more recommendations to consider than we would if we had concluded ‘operator error’ was responsible.

Recommendations in Response to Incident

Continuing with reference to Scenario 2, if we had concluded ‘operator error’ was responsible, we likely would have had one follow up action taking the form of a memo or email to all operators of surgical lasers to ensure the laser is put in standby mode or powered off when not in use.

A method used widely in the patient safety community is the hierarchy of effectiveness of corrective actions as shown in Figure 3.5 Referring to the ‘hierarchy of effectiveness’ of corrective actions, shown in Figure 3, this would be considered ‘inform/educate,’ considered the weakest intervention.

This also reinforces to the entire team that the organization follows up to adverse events with a ‘shame and blame’ approach. It is likely that when the email is sent, everyone knows who exactly forgot to turn off the laser that day.

![Figure 3. Hierarchy of effectiveness of corrective actions, established by the Institute of Safer Medication Practices [5]](https://www.laserstoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Figure-3-e1465960164334.png)

- Equipment: Ensure laser pedals are covered. Consider means of distinguishing ultrasound pedal from laser pedal (geographical separation, visual distinction) to reduce risk of accidental firing.

- Standardize the roles in the OR team, including who is responsible for pre- and post- laser check.

- Training: Outreach aimed at physician group (rounds, explore whether CME points can be awarded for laser safety training).

For Medical Laser Safety Officers that find it challenging to engage physicians in the laser safety program at their facility, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement white paper “Engaging Physicians in a Shared Quality Agenda” provides strong guidance.6

Sharing Lessons Learned

To close the loop, and strengthen the laser safety culture, it is essential to share lessons learned from laser safety incidents. Some methods of sharing include:

- Provide a complete report to administration and the LS Committee and regulating body.

- Write a Lessons Learned report to share with other laser users (not to blame but rather to point out contributing factors and corrective actions).

- Incorporate case studies in laser safety training.

- Present the adverse event and lessons learned at a conference.

When other laser users see the ‘systems approach’ taken in response to adverse events, they will be more likely to come forward and report adverse events.

It is important to stress that this methodology can be applied to ‘near misses’ or ‘close calls’ with equally as rich learning. This is, of course, the preferred method of learning, when harm has not occurred. A non-punitive response to adverse events will have a positive effect on the reporting culture, including the reporting of ‘near misses’ or ‘close calls.’

Conclusions

It is a worthwhile exercise for Medical Laser Safety Officers to become skilled at applying current methodology used in patient safety to learn from adverse events. Taking a systems approach, and identifying the many contributing factors detailed in Figure 2, leads to constructive change and improvement to the laser safety program.

References

[1] Dekker, Sidney (2006), The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error.

[2] Moseley, Harry, (2004) Operator error is the key factor contributing to medical laser accidents” Lasers in Medical Science 19; 105-111.

[3] Kletz, Trevor A. (1993) Lessons from disaster, How Organizations Have No Memory and Accidents Recur. Gulf Professional. ISBN 978-0884151548, p510.

[4] Canadian Patient Safety Institute (CPSI). (2012) Canadian incident analysis framework, p 44.

[5] Duchscherer C., Davies, J.M. (2012) Systematic Systems Analysis: A Practical Approach to Patient Safety Reviews” Health Quality Council of Alberta (HQCA). Available online at www.hcqa.ca

[6] Reinertsen JL, Gosfield AG, Rupp W, Whittington JW. (2007) Engaging Physicians in a Shared Quality Agenda. IHI Innovation Series white paper. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; (Available on www.IHI.org)

Jodi Ploquin is a Certified Laser Safety Officer (CMLSO) specializing in medical, academic and commercial applications in laser safety with KRMC Inc. Liz Krivonosov is President of KRMC, a firm specializing in the risk management of hazardous materials. She is a Professional Engineer and a Certified Industrial Hygienist.